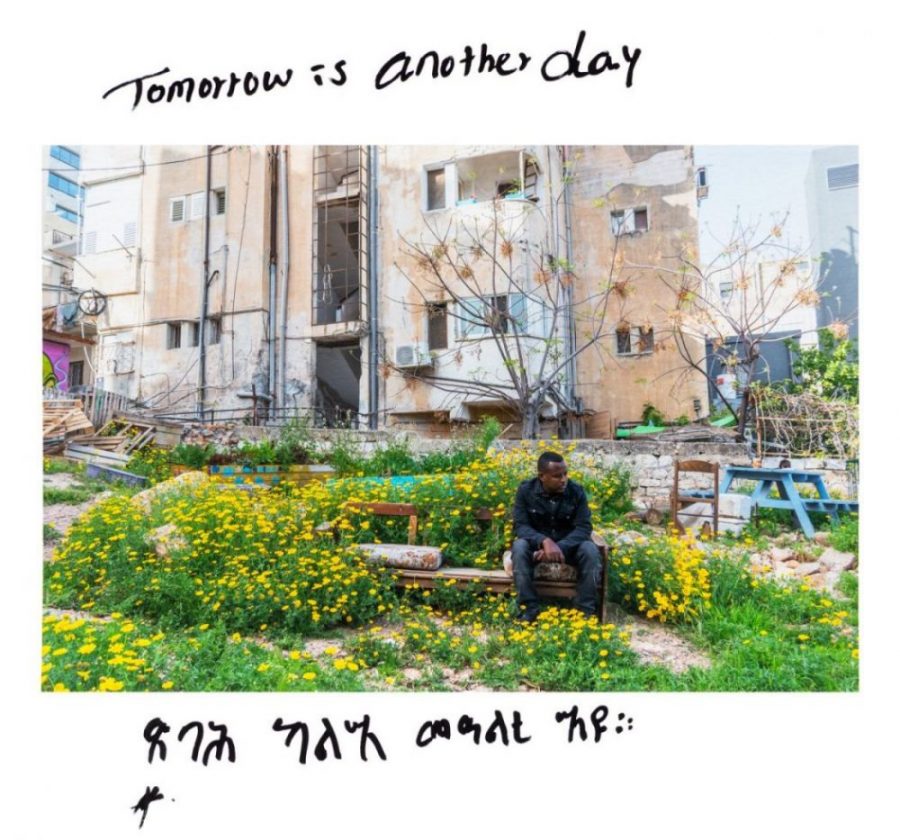

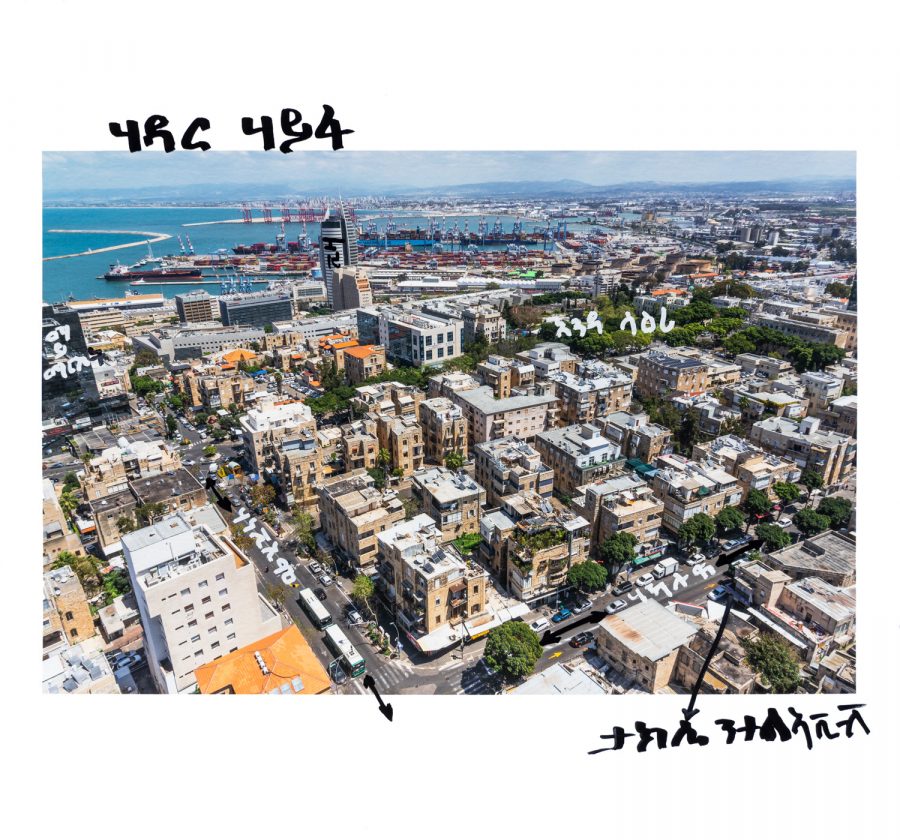

In Hadar Going Nowhere

Daniel Rolider

February – June 2021 — Hadar, Israel

About this series

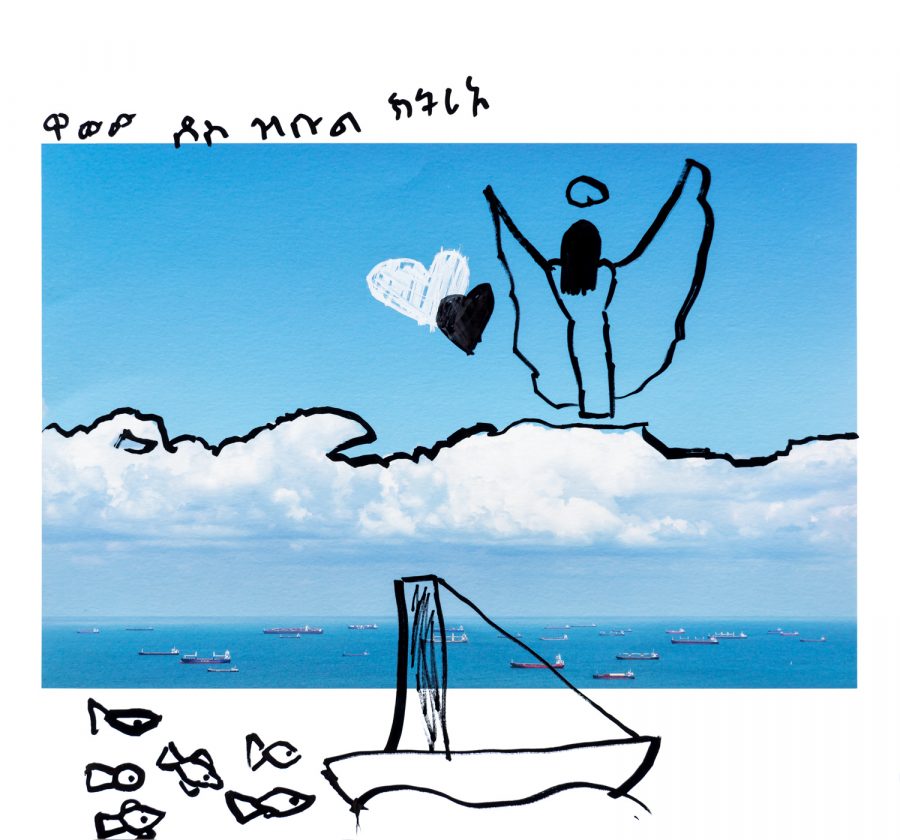

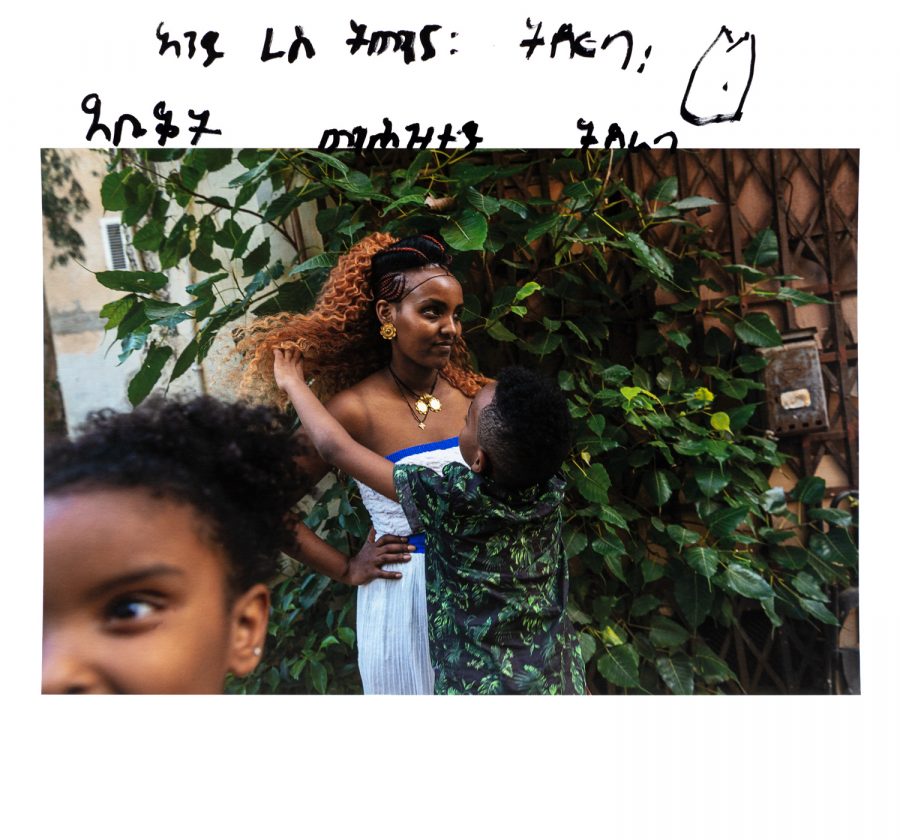

In the Hadar neighborhood of Haifa, in old houses that are now only remnants of a golden age that has long passed, lives a community of Eritrean asylum seekers. Between 500 and 700 Eritreans live in Hadar, one of Haifa’s poorest neighborhoods, out of approximately 21,000 currently living throughout Israel. They live under the radar without basic rights, such as access to healthcare and welfare services, in an endless limbo. On the one hand, Israel cannot deport them due to international laws that grant protection to individuals who meet the consensus definition of a “refugee”. On the other hand, the government has not been approving asylum applications for Eritreans. By combining documentary photography with written dialogue from men and women, single and married, from the Hadar community of Eritrean asylum seekers, this project aims to shed light on the harsh reality that they have been forced into, as well as the reality they

.created for themselves

Photographer: Daniel Rolider

Nationality: Israeli

Based in: Israel

Website: www.danielrolider.com

Instagram: @daniel_rolider

Daniel Rolider is a photojournalist and visual storyteller whose work focuses on environmental and social issues. Born and raised in Kiryat Tivon, Israel, he began his career after completing his mandatory military service as a marine mechanic in the Israeli Navy, and has since worked for the New York Times, Getty Images, ESPN, and Stern, covering stories from his home country. His work has been published in the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, Libération, Der Spiegel, and Haaretz, and has been exhibited in museums and galleries in Israel, the US, China, France, and Greece