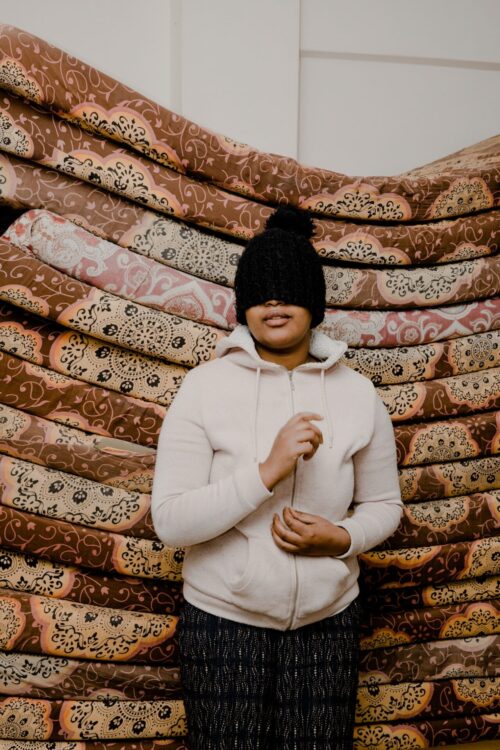

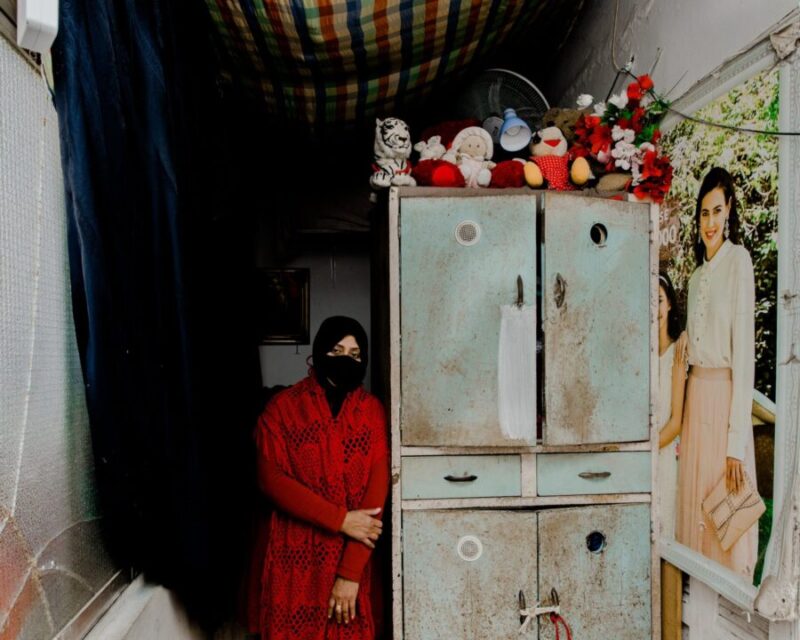

Migrant Workers in Lebanon

Myriam Boulos

2025 — Beirut, Lebanon

About this series

Migrant workers in Lebanon face precarious conditions under the kafala (sponsorship) system, which requires each worker to have a Lebanese sponsor. This system gives sponsors significant control over workers’ lives, often leading to overwork, underpayment, and denial of basic rights such as healthcare and freedom of movement.

As of 2025, an estimated 176,500 migrants live in Lebanon, about 70% of whom are women. Half of them are domestic workers living with their employers, frequently under harsh conditions. Racism and discrimination are widespread, and abuse has become so normalized that even the most extreme cases draw little attention. The recent Israeli war in Lebanon worsened their situation, with many workers abandoned by employers, left homeless or trapped in dangerous areas.

Photographer Myriam Boulos, assigned by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), documented the lives of female migrant workers in shelters supported by the organization. She also captured the work of MSF staff at a clinic in Burj Hammoud, a northern Beirut suburb, where MSF provides basic medical care, sexual and reproductive health services, and mental health support, including psychiatric consultations. During the conflict, MSF partnered with migrant community leaders to reach the most vulnerable individuals in overcrowded shelters and apartments. Mobile clinics were deployed to deliver medical aid, and essential relief items were distributed. This initiative highlights both the urgent needs of Lebanon’s migrant workers and the efforts being made to support them in the face of systemic neglect and crisis.

(In collaboration with Magnum Photos and MSF)

Photographer: Myriam Boulos

Nationality: Lebanese

Based in: Beirut, Lebanon

Website: www.myriam-boulos

Instagram: @myriamboulos

Myriam Boulos was born in 1992 in Lebanon. At the age of 16, she started to use her camera to get closer to reality. She graduated with a master’s degree in photography from the Lebanese Academy of Fine Arts in 2015. She has taken part in both national and international collective exhibitions, including Close Enough at ICP, New York; Infinite Identities at Huis Marseille, Amsterdam; and Troisième Biennale des Photographes du Monde Arabe, at l’Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris.

Her work has been published in Aperture, FOAM, Time, GQ Middle East, Vogue Arabia, and Vanity Fair France, among other publications. In 2020, Myriam co-founded and became the photo editor of Al Hayya, a bilingual magazine that publishes literary and visual content on the works, interests and strife of women in her region. In 2021, she joined Magnum as a nominee. In 2023, her book What’s Ours was published by Aperture and she was awarded the W. Eugene Smith Fellowship.